- San Francisco Chronicle February 14, 2020

- The Times of London May 10, 2012

- The New York Times December 16, 2010

- The New Yorker September 27, 2010

- New York Magazine October 6, 2010

- The New York Times October 6, 2010

- The New York Times February 5, 2010

- The Boston Globe May 15, 2009

- The Sydney Morning Herald December 28, 2009

- The Sydney Morning Herald May 19, 2009

- The Chicago Tribune November 17, 2008

- Time Out Chicago November 13-19, 2008

- Chicago Sun-Times November 15, 2008

- The Irish Times October 4, 2008

- The Independent October 3, 2008

- Irish Times September 29, 2008

- ArtForum: Best of 2007 December 1, 2007

- The New York Times Magazine December 9, 2007

- The New York Times September 16, 2007

- The Village Voice September 12-18, 2007

- The Bulletin September 4, 2007

- Publico July 4, 2007

- Die Presse June 17, 2007

- Klassekampen December 12, 2006

- Variety October 1, 2006

- Neue Zürcher Zeitung August 28, 2006

- Landboote August 28, 2006

- Tages-Anzeiger August 28, 2006

- Het Parool June 16,2006

- 8Weekly June 16, 2006

- Trouw June 16, 2006

- Walker Art Center interview June 8, 2006

- NRC Handelsblad June 2, 2006

- De Volkskrant May 29, 2006

- Le Soir May 24, 2006

- Yale Alumni Magazine November/December 2005

Is This Town Big Enough For Two Gatsbys? Maybe Not

by Jason Zinoman

“The Great Gatsby,” F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic Jazz Age portrait of Long Island society, has been a notoriously difficult novel to adapt, but it hasn’t been for lack of trying. Besides three films based on the book, the last decade has seen an underwhelming opera, a forgettable television movie and a film called “G” in which Jay Gatsby is imagined as a P. Diddy-like mogul named Summer G.

There have been more versions, of course, including a 1926 Broadway play, which ran for four months, but it’s safe to say that none have been as boldly experimental as “Gatz,” produced by Elevator Repair Service, a beloved downtown stalwart whose collaborative shows often include found text, high technology and a brainy, subversive sense of humor. When he began working on “Gatz,” John Collins, the bookish artistic director of the troupe and director of the show, confronted the thorny question that every person who adapts a novel into a play must face: What to cut?

Since the book is so tautly written, Mr. Collins and his associate director, Steve Bodow, had trouble figuring out an answer until they came up with a radical idea: keep it all, every “and,” “he said” and punctuation mark from the 1995 Scribner paperback edition. At six and half hours, including three intermissions, “Gatz” is one of the most faithful adaptations in the history of theater. Falling somewhere between a reading and a conventional play, it is certainly an unusual theatrical experiment, but not unprecedented.

In a routine that has grown legendary, the comedian Andy Kaufman, a longtime inspiration for the company, was known to walk onstage at a comedy club, take out a copy of “The Great Gatsby” and read chapter after chapter until his bored audience walked out in revolt. The difference is that “Gatz” is not a stunt and audiences have not only been staying in their seats but raving about it later.

After seeing an early workshop in January 2005, Oskar Eustis, the Public Theater’s artistic director, immediately wanted to produce it. “It preserves something you almost never see onstage, which is the novelist’s voice,” he said. Mark Russell, one of the most experienced and well traveled downtown producers, said it was the best show he had seen last year.

“Gatz” has been on the international avant-garde circuit, earning good reviews in Brussels and Amsterdam over the last few months. But despite the encouraging notices and adoring producers, New Yorkers will not get to see this production — at least not in the near future. Out of courtesy to another version of “The Great Gatsby,” the F. Scott Fitzgerald estate barred Elevator Repair Service from presenting “Gatz” in its hometown.

The more traditional “Gatsby,” adapted by the California playwright Simon Levy, opens July 21 at the Guthrie Theater’s new $125 million complex on the bank of the Mississippi River in Minnesota. The conflict arises because that show, which runs about two and a half hours, has hopes of moving to Broadway.

“We are concerned that ‘Gatz’ would be confused with the other ‘Gatsby,'” said Phyllis Westberg, an agent for Harold Ober Associates who represents the Fitzgerald estate.

Ever since Mr. Collins approached the estate two years ago, he knew that another show’s producers had an option on the book. But in the fast and loose world of downtown theater, such legal niceties are occasionally ignored. Moreover, he was assured by a representative of the estate that it wasn’t an exclusive contract, and he assumed, naïvely, that getting the rights would be a mere formality.

“It didn’t seem likely that the other show was going to be in New York in January of 2005, which is when we wanted to open,” Mr. Collins said. “At that point, we knew there would be some risk involved, but it was a friendly relationship.”

Then, in the winter of 2004, Mr. Collins received a call from Ted Rawlins, whose Dee Gee Entertainment had the commercial option on “The Great Gatsby.” According to Mr. Collins, Mr. Rawlins told him to continue with the show but said he should do it much later. Mr. Collins protested, arguing that an experimental production with a running time more than twice the length of two football games would pose no threat to a commercial blockbuster. Mr. Rawlins disagreed, Mr. Collins explained. “He said: ‘You’re selling yourself short. We looked on your Web site and saw that you get really good press. That’s not good for us.'”

When reached by phone, Mr. Rawlins described the call differently. “He called me first,” he said. “I just wished him well, and it was a nice conversation.”

At around this time, relations with the estate also started to break down, so Mr. Collins tried to get around the rights problem by presenting the show as a workshop. Friends, producers and other theater people were invited, but there was no advertising, no critics and no admission — although if people wanted to drop a few dollars in a jar at the front of the theater, who was to stop them?

By taking the show underground, Elevator Repair Service burnished its hipster credentials, especially since the audience was full of industry players like Mr. Eustis; Jim Nicola, the New York Theater Workshop’s artistic director; and Wallace Shawn. “It became the place to go, a secret hit,” said Mr. Russell, who produces the annual Under the Radar festival, a showcase that presented the workshop. “If you were really cool, you had seen ‘Gatz,’ but you had to know someone who knew someone who knew someone.”

Unfortunately for Elevator Repair Service, one someone happened to be a trustee of the F. Scott Fitzgerald estate, who alerted Ms. Westberg, who promptly sent a cease-and-desist e-mail message. That was the end of “Gatz” in New York.

The tale of the two “Gatsbys” is not just about two very different productions but about two theories of adaptation. Mr. Levy, who has adapted two other Fitzgerald novels — “Tender Is the Night” and “The Last Tycoon” — for the Fountain Theater in Los Angeles, where he is the producing director and dramaturg, said adaptations of Fitzgerald are generally too reverential.

“The problem with other adaptations is they take the passion out of the characters,” he said. “The scenes are slo-o-o-ow and moody. People in the 1920’s had stinky feet, too.” With an African-American saxophonist and 18 actors, his show, he said, will have the size and scale of a musical.

By contrast, Mr. Collins’s approach suggests that adapters are sometimes not worshipful enough. “Adapters are impatient,” he said. “They follow a conventional set of rules and always think: how can we get back to the plot? Our idea was to treat the book like the Bible.”

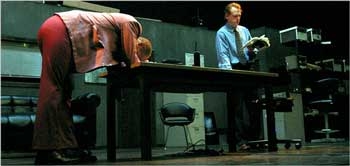

To give a sense of the production, Mr. Collins showed an abbreviated tape of “Gatz” at the Fort Greene offices of Elevator Repair Service, whose name comes from a career-placement test a young Mr. Collins took that suggested he repair elevators for a living. “Gatz” takes place in a depressed modern office. A beleaguered white-collar employee, played by Scott Shepherd, enters, picks up a copy of “The Great Gatsby” and starts to read. He doesn’t stop.

At first, his co-workers don’t seem to notice, but as the show progresses, parallels start to emerge between people in the office and characters from the book. Mr. Shepherd, for one, acts out the role of Nick Carraway, the narrator. A Jay Gatsby type (played by Jim Fletcher, a veteran of Richard Maxwell’s plays) enters wearing a white suit and a yellow tie. Sometimes actors interrupt the reading to recite dialogue, often engaging in scenes with one another. Before you know it, the show shifts from a man reading “Gatsby” to a performance of “Gatsby” staged around the man.

This idiosyncratic style, company members say, wouldn’t work for every novel, but the combination of the book’s prominent narrator, evocative prose and relative brevity made “Gatsby” a natural fit. “I was most skeptical,” said Mr. Bodow. “But the first time we tried it, I realized that, yes, you can say it all.”

By June 2005, Mr. Collins and Mr. Bodow managed to persuade the estate to allow them to produce the play anywhere but Britain and the United States, where specific permission is required. When they asked about a New York Theater Workshop production for January 2007, Ms. Westberg said no.

Mr. Eustis thought he could get approval for a production at the Public because he and Simon Levy were old friends. But despite conversations with Mr. Levy, lawyers for the estate and the director David Esbjornson, who will remount “Gatsby” at the Seattle Rep in the fall, Mr. Eustis said, “I exerted my apparently inadequate influence and got nowhere.”

“Gatz” will have its American premiere at the Walker Arts Center in Minnesota on Sept. 21, less than two weeks after “The Great Gatsby” closes at the Guthrie. Mr. Collins is still fixated on New York, not only because the company is based here but also because a production at the Public would be a major breakthrough for his company, which is relatively unknown outside theater circles.

And while he wishes the other show good luck — or so he says — Mr. Collins knows that his best hope is if the critics hate the “Gatsby” in Minnesota in July, and its Broadway dreams die a quick death.

“That Oskar wants to do it is a huge deal for us,” he said, “and the fact that we can’t do it in our hometown is heartbreaking.”

To read this article on the New York Times website, click here.