- San Francisco Chronicle February 14, 2020

- The Times of London May 10, 2012

- The New York Times December 16, 2010

- The New Yorker September 27, 2010

- New York Magazine October 6, 2010

- The New York Times October 6, 2010

- The New York Times February 5, 2010

- The Boston Globe May 15, 2009

- The Sydney Morning Herald December 28, 2009

- The Sydney Morning Herald May 19, 2009

- The Chicago Tribune November 17, 2008

- Time Out Chicago November 13-19, 2008

- Chicago Sun-Times November 15, 2008

- The Irish Times October 4, 2008

- The Independent October 3, 2008

- Irish Times September 29, 2008

- ArtForum: Best of 2007 December 1, 2007

- The New York Times Magazine December 9, 2007

- The New York Times September 16, 2007

- The Village Voice September 12-18, 2007

- The Bulletin September 4, 2007

- Publico July 4, 2007

- Die Presse June 17, 2007

- Klassekampen December 12, 2006

- Variety October 1, 2006

- Neue Zürcher Zeitung August 28, 2006

- Landboote August 28, 2006

- The New York Times July 16, 2006

- Het Parool June 16,2006

- 8Weekly June 16, 2006

- Trouw June 16, 2006

- Walker Art Center interview June 8, 2006

- NRC Handelsblad June 2, 2006

- De Volkskrant May 29, 2006

- Le Soir May 24, 2006

- Yale Alumni Magazine November/December 2005

Textual Fidelity Reborn Through The Medium Of Soap Opera

by Tobi Müller

Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” is required reading in America. A company from New York reads it word for word at the Theaterspektakel — and gradually begins to perform it, as if in a film. Quiet, long, funny.

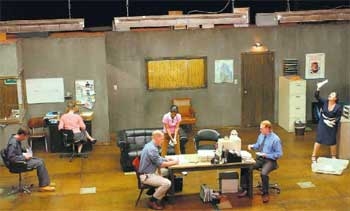

A lonely room. File cabinets, an inner office with windows looking in. A typewriter sits across from a computer. Faint big-city noise, it’s morning, a man begins his humdrum day. But the computer won’t start. He finds a book wedged in an old rolodex. He is alone and reads the first sentence out loud in a low voice. It’s the beginning of a transformation: from broker to bookworm. It is the transformation of the narrator Nick Carraway (Scott Shepherd). Later, as the number of actors grows to twelve, things occasionally get loud and messy. By the end things have reached soap-opera proportions.

The first part, which was performed in the Rote Fabrik on Thursday, lasts almost three-and-a-half hours. Elevator Repair Service, a theater company from New York, doesn’t leave out a single sentence from the American school-reading-list novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald, “The Great Gatsby,” published in 1926. At the Theaterspektakel the evening is called “Gatz”: the shady title character’s name before he lived in wealthy splendor on Long Island — when he was still growing up poor in North Dakota.

All-clear: The duration is not a problem

The fact that we can sound an immediate all-clear signal to your sitting flesh for the majestic duration is thanks to a rare (at least in our conception of theater) hybrid form. That inane term “textual fidelity” (there is no such thing: every step on the stage is a step away from the text) is dutifully fulfilled and challenged at the same time. Those with a very good understanding of English can actually take pleasure in Fitzgerald’s rhythm, that unobtrusive language-enamored “flow” that is always so much harder to achieve in German.

It’s a flow of language that celebrates the rapidly developing opulence of the Jazz Age and glorifies the foundations of American Henry-Fordism as something beautiful. But it also already warns against the moral collapse of historyless materialism. And on a figurative level, Gatz’s rebirth as Gatsby, which as a “rebirth” takes on a religious dimension, comes damn close to heresy. Scene summaries are provided on an electronic screen; nevertheless, without a firm grasp of English you miss a lot.

On the other hand, the group, which eventually grows to twelve actors, zips around the reader/narrator and creates an atmosphere of resemblances: the events on stage often, and more and more closely, reflect the novel’s action as it is read; everyone plunges into the book collectively as if eager to throw away their day-to-day office lives. The switches from office to novel and back again are synchronized so precisely however, and at the same time so nimbly, that there is hardly ever a rough seam.

Comedic soundscape

Perhaps this very perfection is the one small problem for this unvain company (vanity would treat the text as a sacred thing immediately, which in this radically conservative form, and with this duration, would be intolerable). The structure of entrances does grow somewhat predictable, and sometimes the bringing close of stage and text only succeeds in bringing them close. Few non-Americans will know that the comedic soundscape and a few of the performers are quoting straight out of the so-called screwball comedies produced by Hollywood chiefly in the 1930s. When Gatsby’s former love Daisy weeps for joy in a pile of Gatsby’s expensive shirts, we Europeans get a hint of this commercial but also acidly anarchic tradition.